Article

| Violence prevention : schools and communities working in partnership by Phillip T. SLEE, Professor in Human Development, School of Education, Flinders University of South Australia Theme : International Journal on Violence and School, n°1, May 2006 Institution : School of Education, Flinders University of South Australia |

| Within recent years there has been an increasing global concern with school violence. A range of publications and international conferences have highlighted the issue in Europe, (eg, European Commission CONNECT project on Violence in Schools www.gold.ac.uk), Canada, (Canadian Initiative for the Prevention of Bullying www.cipb.ca) and the Asia-Pacific Rim (eg, Keeves & Osako, 2003). In Australia, the issue of school violence is presently attracting more in the way of media, research and government policy attention. There is no doubt that school violence is well and truly on the agenda for researchers and as will become apparent this represents a general shift in understanding of the issues involved over the last decade. |

Keywords : .

English text (dowload the PDF file here)IntroductionWithin recent years there has been an increasing global concern with school violence. A range of publications and international conferences have highlighted the issue in Europe, (eg, European Commission CONNECT project on Violence in Schools www.gold.ac.uk) Canada, (Canadian Initiative for the Prevention of Bullying www.cipb.ca) and the Asia-Pacific Rim (eg, Keeves & Osako, 2003). In Australia, the issue of school violence is presently attracting more in the way of media, research and government policy attention. There is no doubt that school violence is well and truly on the agenda for researchers and as will become apparent this represents a general shift in understanding of the issues involved over the last decade. Presently the idea that violence is not simply a school problem but rather a wider community issue is gaining currency (Randall, 1996; Cunningham & Sandhu, 2000; Slee,2001). There are in fact significant advantages to nesting the issue of violence in a broad community context. For example, it is a less blameful orientation than considering it only as an organisation problem, which must be solved by education and school authorities. The fact that it is being seen also as a community issue is reflected in the growing number of organisations expressing concern about the issue. For example, in Australia organisations such as ‘Safety House”, Child Help-Line, and the Department of Community Services through ‘Parenting South Australia” are just a few examples of where the issue of violence has been addressed in the broader community context. The movement toward the wider community initiative is underpinned by the writing of authors such as Etzioni (1995) and Tam (1996). In advocating a movement toward ‘communitarianism, ' Etzioni (1995) describes the 'social webs of communities' as the webs that bind individuals, otherwise isolated, into groups who care for one another and who help maintain a civic, social and moral order. A related concept to that proposed by Etzioni (1995) and Tam (1996) is the argument that school violence detracts from the ‘social capital' of a society (Coleman, 1988; Cox,1998). Social capital was seen by the late James Coleman as an ingredient of the functioning of social relations among individuals. Significant elements of social capital include the extent to which individuals trust and have confidence in each other in the general community. As such, social capital is a resource residing in the social networks of the members of a community. Researchers are now examining the links between social capital and school outcomes including students ‘at-risk' for being victims or perpetrators of violence (Runyan et al, 1998). The complexity of the debate regarding whether school violence should be addressed from within the school itself or whether it should be considered in broader community terms has received some significant limited discussion( eg Debarbieux, Blaya, & Vidal, 2003; Sebastiao, Campos, & deAlmeida,2003; Roland, Bjornsen & Mandt, 2003). Background

In a paper published in 1990 by the Australian Institute of Criminology addressing the issue of violence in broader Australian society the members of the committee note a number of common factors associated with violence in Australia. The violence tends to be (i) much greater for males (ii) higher in urban areas (related to economically disadvantaged areas (iii) associated with young adults (iv) linked in terms of victimisation to Aboriginality. Compare this to the similarity in Webber's (1997) overview of commonly mentioned factors associated with school violence, including (a) family factors including economic status (b) individuals factors such as difficult temperament and (c) societal factors such as educational opportunities. Violence in Schools Whilst internationally there is a good deal of discussion of the issue of violence in schools (eg Smith, 2003) the matter is also the focus of attention in Australia as attested to by media reports and more significantly by major Federal and State inquiries (eg Sticks & Stones,1994). Initiatives at the Federal level include the National Safe Schools Framework where the major issues canvassed are bullying, harassment, violence and child protection www.mceetya.edu.au/pdf/natsafeschools.pdf to be elaborated on later. At the state level one recent initiative is that of the South Australian Department of Education Training and Employment's (DETE) (2005) establishment of the ‘Coalition Against Bullying”. This is intended for all South Australian Schools as a resource to help them access experts and resources on school safety and security. To appreciate why school violence is fast emerging as an educational issue it is necessary to see it in the broader international context and in relation to contemporary dominant themes of social change in Australian culture, including those of patriarchy, authoritarianism, masculinity, racism and feminism. As part of the ‘global village' Australia is not unaffected by international events. Certainly the well publicised school violence in the United States of America and Canada have sensitised Australians to the issue. The April 1999 Columbine School shootings in the United States of America resulting in the death of 12 students and 1 teacher and the wounding of 23 others captured media headlines in Australia. Similarly the shooting of a student in Taber school in Alberta Canada was highlighted in the media. In May 1999, following the Columbine shootings a number of boys were suspended from different schools in New South Wales for creating a ‘massacre list' of students and teachers .

Generally, Australia has many features in common with other countries when it comes to the issue of violence. Consideration here is given to:

It will be argued that systemic school/community partnerships as a focus for addressing school violence have a number of advantages in terms of prevention and intervention. Definition of Violence In 1994 an Australian Federal Senate inquiry resulted in the publication of an influential paper ‘Sticks and Stones: A report on violence in schools'. This inquiry heralded a nationwide movement to address the issue of school violence, particularly bullying. The inquiry raised significant questions regarding the frequency of violence in Australia, the impact of violence on the community, and identified the need for evidence based intervention programs to reduce violence.

In the book ‘Violence in Schools' (2003) some of the significant issues associated with the definition of violence are considered. Smith (2003) identifies the need for definitions of violence to be contextualised "… in the multiple contexts of family, peer culture, the school's community, the society in which the community is located, and increasingly in the context of the global environment of international co-operation, international conflict, scientific and technological progress, and environmental degradation” (p.1). In terms of the issue of school bullying there is a view is that there needs to be a distinction made between bullying and violence. The accepted definition of bullying is that it is widely regarded as a particularly destructive form of aggression. It is defined as physical, verbal or psychological attack or intimidation that is intended to cause fear, distress or harm to the victim, where the intimidation involves an imbalance of power in favour of the perpetrator. Typically there are repeated incidents over a period of time (Slee, 2001). Distinguishing features of this broadly accepted definition relate to the power imbalance and the repetition over time. See Mooij (2005) for a recent discussion of the definition of violence and the distinction between violence and bullying. It would be a helpful step forward for countries to reach some consensus regarding definitional issues. Knowledge Regarding School Violence The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) collates statistics regarding recorded crime in Australia. In examining the location data for Australian crime reports relating to ‘assaults' for the year 2000 it is apparent that the majority of assaults occur in private dwellings (34%), in the community (23%) in recreational areas (10%) retail area eg shop (7%) , in areas of justice eg police stations and courts(4%) and in education areas (3%). These figures reinforce the point that violence is a school/community issue. The figures suggest that education areas are a source of violence occurring in the top 10 places. In a 1990 Australian Institute of Criminology report it was noted that it is often schools where aggressive or otherwise anti-social behaviour first becomes publicly apparent. South Australia has a computerised method for recording school-based incidents which it has kept since 1999. For example, the majority of suspensions in term 3 of the school year in 2002 were for (i) threatening the good order of the school (42%); interfering with the rights of others (7.2%) and threatening or perpetuating violence (28.7%). It could be argued that seen that under the broad rubric of ‘threatening the good order of the school' it is possible to get some understanding of the level of school violence. In Australia, the difficulties inherent in collating statistics on school violence mirror those reported by many other countries (Smith et al,1999, Smith, 2003). For example, differences in definition, data collection and collation methods mean that it is difficult to compare figures across the states and territories in Australia. In 1994 a Federal Government inquiry into violence in Australian schools concluded that while violence was not a major problem in Australian schools, bullying was. A recommendation of the inquiry was for the development of intervention programs to reduce school bullying. School Bullying and Violence Outcomes of the international efforts to understand the nature of school bullying have resulted in significant publications such as that by Smith et al (1999) which have drawn together the findings of research from over 22 countries. Bullying is widely regarded as a particularly destructive form of aggression. The evidence is now quite clear from both national and international studies (Smith et al, 1999; Smith, 2003) that bullying in schools is an international problem. Emerging evidence shows that young people's mental and physical health are strongly influenced by the school social environment (Resnick, 1997). In a meta-analytic review of twenty years of research Hawker & Boulton (2000) concluded that it was clear that victimisation was positively associated with depression, loneliness, anxiety and low self esteem and poor social self concept. They conclude by noting that cross-sectional studies " … demonstrate that victims of peer aggression suffer a variety of feelings of psychosocial distress. They feel more anxious, socially anxious, depressed, loneliness and worse about themselves than nonvictims” (Hawkins & Boulton, 2000,p.453). They go on to note that "The evidence suggests that these feelings occur among victims of both sexes, of all age groups, and of all subtypes of aggression' (p.453).

The research of the last 25 years confirms its widespread nature where it is particularly likely in groups from which the potential victim cannot escape eg schools. The international research suggests that despite some cultural differences many of the broad features of bullying are similar across different countries (Smith et al, 1999; Slee et al, 2003). For example, there appear to be characteristic sex differences with boys using and experiencing more physical means of bullying and girls experiencing or using more indirect and relational means. It is also commonly found that many victims do not report bullying or seek help. Research from the Asia-Pacific rim (Slee,2003) involving Australia, China, Japan, Korea and new Zealand has highlighted how cultural and historical influences have shaped how school bullying is viewed and further cross cultural research in this region is warranted to build on Japan's long history of research into this phenomenon as exemplified by the pioneering work of Morita (1985). Bullying in Australian Schools As noted earlier bullying, involving a power differential and ongoing perpetrator-victim relationship, is a specific manifestation of violence. Generally violence is defined in terms of intention to hurt others. The violence literature originally studied physical and verbal aggression, with boys as the main perpetrators and victims. However, more indirect, or social, forms of violence are now also recognised, in which the perpetrator intends harm through manipulating others' peer relationships. Significant research (eg Salmivalli, 1996) has prepared the way for understanding victimisation in terms of group processes.

In 1991 Rigby & Slee published the first Australian report on the incidence of bullying among students (N=685) between 6 and 16 years of age in a sample of South Australian schools. Self-reports of being personally bullied by other students ‘pretty often' provided a figure of 13 percent for females and 17 percent for males. Since the initial study data collected using anonymous surveys for 25399 students ranging in age from 8 to 18 years from over 60 schools around Australia indicates that over 20% of males and 15% of females report being bullied ‘once a week or more often' (Rigby, 1996; Rigby & Slee,1999). This data base is continually being up-dated.

N = 13,977 N = 10,560 Table 1. Incidence of victimisation according to age; students reporting being bullied ‘at least once a week' in co-educational schools in Australia. Reproduced from Rigby & Slee,1999 The findings for the form of bullying for the sample of 25399 Australian students is presented in Table 2.

8-12 Years 13-18 Years Never Some- times Often Never Some-times Often Being Teased Boys 50.1 38.0 11.9 52.6 38.0 8.6 Girls 52.6 38.8 8.6 58.1 33.5 8.4 Hurtful Names Boys 49.7 36.4 13.9 56.0 33.1 10.8 Girls 49.6 38.4 12.0 56.7 33.2 10.1 Left Out Boys 65.9 26.9 7.3 75.7 18.8 5.5 Girls 58.7 32.3 9.0 69.0 24.4 6.6 Threatened Boys 71.5 22.7 5.8 74.4 19.8 5.9 Girls 84.9 12.6 2.5 87.8 9.7 2.5 Hit/Kicked Boys 63.5 28.5 8.0 72.4 21.3 6.3 Girls 77.2 18.9 3.9 88.5 9.3 2.2 Boys 3320 10657 Girls 2587 6973 Table 2. Percentages of school children reporting being bullied by peers in different ways, according to gender and age group. Reproduced from Rigby & Slee,1999 From Table 2 it can be seen that bullying may be physical, verbal or psychological. Physical bullying occurs more with boys and emotional and emotional bullying occurs more often for girls. The Australian research of Owens and MacMullin (1995) has provided insight into the nature of girl's aggression and to the damaging effects of indirect or relational aggression in peer relationships. As Owens and MacMullin (1995,p.34) have concluded "… there are gender and developmental differences in aggression among students. More specifically, boys used more physical aggression strategies than girls and older girls used more indirect forms of aggression than boys”. This research finding mirrors that of many other countries. Only recently has research in the more broadly-defined field of aggression begun to address the issue of cross gender aggression. Crick, Bigbee & Howes (1996) found that 9-12-year-old students agreed that the commonest form of cross-gender aggression was the verbal insult. Paquette & Underwood (1999) asked young adolescents to provide examples of various types of aggressive incidents they had suffered: over 20% of boys and over 30% of girls gave cross-gender examples. Although physical aggression for boys was almost always from other boys, in nearly half the incidents of physical aggression towards girls, boys were the perpetrators. Furthermore, frequency of being subject to social aggression impacted more strongly on girls than boys, being more strongly negatively correlated with various aspects of self-concept. Research (Owens, 1998; Russell & Owens, 1999) has shown that, although boys are less socially aggressive to same-sex peers than are girls, when boys are aggressive to girls, they display more social aggression, especially in the older high-school age group (Russell & Owens, 1999). Also, girls sometimes recruit boys to participate in socially aggressive vendettas against other girls (Owens, Shute & Slee, 2000a). Little else is known about the detailed nature and dynamics of boy-girl social aggression. Researchers have speculated that for boys, within their large, loose groups, hierarchy and dominance issues lead to physical aggression and verbal abuse; by contrast, girls are more likely to hurt others through attempts to disrupt their closer, more intimate relationships with other girls (e.g., Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). This speculation has been directly investigated, within adolescent girls' groups, by Australian researchers (Owens, Shute & Slee, 2000a; 2000b; Owens, Slee & Shute, 2000). The reasons girls gave for social aggression included group processes concerning intimacy and acceptance. Witnesses often failed to defend victims, or even joined the aggression, unable to resist the power of the group and fearful of becoming the next victims. Uncovering such detail about perceptions of group processes is crucial for devising appropriate interventions (Owens, Slee & Shute, 2001).

In a 2003 a community based study by the author of 1479 Australian high school students from 5 schools a number of insights into the nature of same sex and cross-sex aggression was obtained. Overall, this study showed that adolescents held different perceptions of the nature of ‘unwanted' aggressive behaviours directed toward same-sex and opposite sex students. The findings were consistent with those reported by Crick et al (1996) involving younger students that verbal abuse was a very common form of cross-sex unwanted behaviour. The findings were also consistent with those of Paquette and Underwood (1996) that cross-sex physical aggression was quite common. The findings from this analysis are presented in Fig. 1.

These results indicate that: (i) males engage in more aggression than females Overall as predicted males engage in more aggression than females and females receive more verbal aggression than males. The findings generally confirmed the previous research of Bjorkqvist et al (1992) and Owens (1996) that males both perpetrate and receive more physical and verbal aggression than females and females receive more social aggression than males. In terms of cross sex aggression an interesting picture emerges with females directing more physical aggression to males than males to females but males direct more verbal and social aggression to females than vice versa. Girls receive more social aggression than boys. Consistent with Owens (1996) a decline in aggression with age occurred and this applied particularly to verbal aggression. In devising interventions to reduce the harmful effects of cross-gender aggression, it is vital to understand why boys perform these behaviours. Boys' perspectives, as well as those of girls, must therefore be sought. That boys' and girls' views differ is already apparent from the fact that girls report a higher prevalence of boy to girl aggression than do boys (Owens, 1998). Similarly, Tulloch (1995) found that some behaviours which girls view as bullying are seen as harmless fun by boys. Understanding such differing perspectives is crucial for prevention/intervention programs. In Australia, research within sociological and feminist frameworks and in the educational literature has highlighted the importance of broad cultural influences, such as male-female power differentials, on boys' victimisation of girls, especially through sexual harassment (e.g., Gilbert & Gilbert, 1998). Rigby (1998) has speculated that boys may bully to impress girls; it is also possible that they aim to impress other boys. In considering victimisation of girls by boys, sexual harassment may seem an obvious issue, especially in the early high school years, when girls may be particularly sensitive to victimisation based on their developing bodies and sexuality ,indeed, even in preadolescence, a relationship has been found between girls' perceptions of sexual harassment and their body esteem ( Murnen & Smolak, 2000). Bretherton, Allard and Collins (1994) suggest that boys are socialised to believe they have power over females and have observed that even young boys sometimes use sexual aggression against girls and women. Martino (1997) interviewed Australian adolescent boys about their views of masculinity, and concluded that status is conferred by peers on boys who display a particular type of heterosexual masculinity which involves denigrating "anything that smacks of femininity" (p. 39). Martino noted that such social and cultural practices limit the personal choices of both sexes. The sexual harassment literature is a separate one and, in stark contrast to the individualistic approach of the aggression/ bullying literature, broad societal influences are seen as central. The importance of gaining an understanding of boys' perspectives is essential since male attitudes towards violence contribute to resistance to preventive initiatives (Artz & Riecken, 1997). Attitudes to Violence/Bullying A limited amount of research has examined the nature of attitudes toward violence and bullying (Randall, 1995; Rigby & Slee, 1991, Hemphill, Toumbourou, & Catalano, 2005). In a recent study with the ‘5 Schools Project' by the author involving 1479 year 8-10 students from 5 schools an investigation was undertaken into nature of attitudes underpinning the related concepts of school bullying using a standardised attitude scale (Rigby & Slee, 1991). The least provictim students were in year 9 with the most in year 10 with a significant difference between years 9-10. Females were most provictim but amongst the females the least provictim were in year 8 and the most provictim were in year 10.

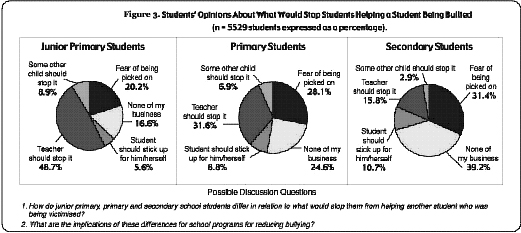

Figure 2. Total Provictim Attitudes by Year Level and Gender Further analyses of experience of bullying and victim empathy was undertaken in this study. It was found that amongst the most frequently bullied students two subgroups existed – those who experience a great deal of bullying and who empathise with its victims and those who also experience high levels of bullying and show little victim empathy. The findings from the present study showed that males held the least provictim attitudes and the year nine male students were the least provictim of all. Generally, the findings are consistent with the idea that the trajectory is for an increasing empathy with the plight of victims of bullying. As Damon (1983) has noted with age the child becomes more sensitive to the ‘general plight' of life's chronic victims, including the poor, the handicapped, the socially outcast. This opens the way for a new domain of prosocial activity with an effort to aid those less fortunate than oneself. The gender differences with females being more provictim than male confirms the research of Frodi, Macawley & Thorne,1977). The unsympathetic attitudes of year nine students could be explained in terms of the increasing exposure to normative pressures that inculcate an unsympathetic attitude towards the victims of bullying. Accordingly, as Askew (1989) has noted, the rules, norms and roles to be followed in schools are stereotypically male ones. It is seen as desirable to be dominant, competitive, ambitious, aggressive and never to show emotional weakness. Support for this view is found inasmuch that there was no relationship between the amount of bullying students reported from same sex and opposite sex peers so it could not be argued that lower provictim scores were due to greater levels of victimization. Salmivalli & Voeten's (2004) research with students aged 9-12 years has highlighted the importance of classroom context and normative beliefs influencing bullying behaviour. They have also shown the impact of gender differences with social context mattering more for girls than boys. Further research is needed in relation to the attitudes of students in terms of informing interventions. Safety From Bullying As already referred to in the definition provided earlier, an important element of the definition of bullying relates to the question of a power imbalance between the bully and victim and so safety at school is a pertinent question. In a large scale sample, Australian students were asked if school is a safe place for ‘young people who find it hard to defend themselves from attack from other students? Among both males and females less than 20% see school as a ‘safe' place for vulnerable students. Of the students who report being bullied at school over 9% report that they have truanted and over 15% report ‘thinking' about staying away from school (Slee,2001). School bullying then raises the question of equity and access for some students in relation to education. Interventions to Reduce Bullying As Elsea & Smith (1998,p.203) have noted "Most, if not all, children experience bullying at some time in their lives: they may be the victim, they may be the bully, or they may witness the suffering of others”. It has already been noted that up to a quarter of the school population may be caught up at any one time in the cycle as either bullies or victims. It begs the question of what the other three quarters of the school population are doing. There is now a significant body of research being looking at the ‘bystander' effect.

Evaluations of interventions to reduce school bullying have met with varying levels of success. There is a growing body of evidence that school based intervention programs can be effective in reducing the level of school bullying. Widely known and well documented evaluations include those by Olweus (1993), Smith (1996) and Pepler, Craig, Ziegler & Charach (1993). Effect sizes for intervention studies include a 50% reduction as reported by Olweus (1993) , a 17% reduction reported by Smith (1996) a reduction of 30% reported by Pepler et al (1993), and a 30 - 40% reduction reported by Slee (2004). Roland (1989) failed to find any reduction in the level of school bullying. Smith, Pepler & Rigby (2004) have recently comprehensively reviewed a range of intervention strategies from various European, North American and Australian research. However, one cannot easily compare the various intervention programs given the range and type of methods used and the procedures employed (Stevens, Bourdeaudhuij & Van Oost, 2000). A key element of interventions is the adoption of an evidence-based approach. This approach warrants that rigorous evaluation be integrated into decisions about interventions by policymakers and practitioners (Commonwealth of Australia, 2000). Secondly, consideration should be given to where the interventions are targeted. Adapting a model described by Mrazek & Haggerty (1994) interventions may be targeted: a) universally at whole populations Thirdly, developmental differences are taken into account in considering interventions. Knowledge about the specific ways in which children's understanding of violence changes as they mature is critical to designing effective programs for prevention and intervention (Debaryshe & Fryxell, 1998). Interventions based on systems theory have a unique contribution to make to school violence prevention. Theoretically systems thinking (Slee & Shute, 2003) is aligned with constructivist thought. It embraces the idea of the ‘social', whereby meaning is constructed within the social setting of relationships, interactions and communication. Using cybernetic theory (Howe & von Foerster,1974) interventions may be considered in terms of ‘first-order' and ‘second-order' change. In terms of ‘first-order' change individuals caught up in a cycle of violence may need some assistance and strategies to deal with bullying. The school system remains the same and if the view of the situation is accurate and constructive, and if in fact the students do simply need to acquire some new skills, then ‘first-order' interventions have a place in an intervention program. There is certainly a well documented body of evidence which attest to the value of such interventions including social skills training(e.g. Owens, Slee, & Shute, 2000). ‘Second-order' change will occur when the system itself begins to change. For example, the school or community may gain some insight through a review of policy and practice as to how the current school procedures maintain and even amplify or encourage violence/bullying. The school community in modifying cognitions, attitudes, perceptions and beliefs may choose to approach the issue of violence from a very different perspective. In shifting focus, and thinking in more systemic terms, change will resonate throughout the school/community system. Instead of concentrating on changing the ‘bad' or problematic behaviour of the bully and on ‘helping' the victim, consideration will be given to relationships, roles and interactions, and communication within the system which encourage or dis-courage violence. When the system itself begins to change or realign, ‘second-order' change has occurred. Systemic thinking is sharply at odds with more conventional western scientific thinking with its emphasis on remediation, deficits and weaknesses in the individual (Slee & Shute, 2003). In contrast to such a ‘deficit' approach, it emphasises the active role of the individual in socially constructing meaning with a strong focus on competency, success and individual strengths. Australia's Approach to School Bullying and Violence: The National Safe Schools Framework. The National Safe Schools Framework (NSSF) provides a national approach to dealing with school violence and bullying and child protection issues in schools. It is guided by the vision that all Australian schools are safe and supportive environments. It consists of a set of nationally agreed upon principles for a safe and supportive school environment. It comprises a set of 11 guiding principles. These have 6 key elements that schools must act upon including:

All Australian schools as a condition of Federal funding are required to put the NSSF into effect by 2006 and report annually on their progress. The web site for the NSSF is www.mceetya.edu.au/pdf/natsafeschools.pdf Community Based Interventions It is now more common place that interventions to address school violence and bullying draw on collaborative school-community partnerships. A guiding principle as elaborated by Lerner et al, (2000,p.27) is that "…a scholar's knowledge must be integrated with the knowledge that exists in communities in order to fully understand fully the nature of human development…”. Partnerships involving universities and organisations are not without their tensions. As Shonkoff (2000,p.528) has noted "Science is focussed on what we do not know. Social policy and the delivery of health and human services are focused on what we should do. Scientists are interested in questions. Scholars embrace complexity. Policy makers demand simplicity. Scientists suggest that we stop and reflect. Service providers are expected to act”. In Australia a number of school-community interventions have been implemented by the author and two of these will now be described as a basis for outlining a process and providing evidence for the efficacy of this approach in addressing school violence. (i) Anti Violence Bullying Prevention Project. In 2000 a two year South Australian community intervention program to reduce bullying in schools was completed. Participating community organisations included schools, the police department, Catholic Education Office, Department of Education, Training and Employment, and Department of Human Services and Flinders University. Representatives from these organisations met regularly to co-ordinate an intervention program in a primary and secondary school, which had volunteered to be involved. Examination of the interventions indicates that they were successful in addressing the issue of bullying in schools, achieving over a 40% reduction of bullying in the primary school and a smaller but significant reduction of bullying in the secondary school. A range of other positive outcomes from this community based intervention included greater student awareness of the issue of bullying, increased confidence in how to manage it and report it and greater feelings of safety at school. Significant efforts were made to reach out to and engage the parents and broader community around the issue. (ii) The Five Schools Bullying Prevention Program. This on-going research project was conducted as part of a University-Industry Collaborative Research Grant involving the University sector, the Department of Health and the Department of Education to highlight best practice interventions used in South Australia to address the issue of school bullying. The 3 year program commencing in 2002 involved regular planning meetings, survey data collection from 1479 students, interviews with key teaching staff and health providers and focus groups with students in each of the five schools. An outcome of the research has been the development of a video/DVD reflecting the views of key participants in the intervention (e.g., students, teachers, parents and community members) regarding the critical elements of an anti-bullying program. The video/DVD will be used as part of a South Australian Department of education initiative to address school bullying. Three Underlying Principles for School-Community Partnerships Three essential principles derived from the author's experience with these programs and the literature underpin school-community partnerships including: (a) the development of a supportive, safe living environment and (b) the realization of the social capital within the community and (c) the actualization of self efficacy for school/community action. (i) Supportive Living Environment All the available evidence points to the basic human need for a safe and peaceable living environment and Australian research (Rigby & Slee, 1999) highlights that less than 20% of students feel that school is a safe place for those vulnerable to victimization. A proactive community oriented approach by which a school engages the police in a safety audit, and the teaching of protective behaviors is more effective than any punishment oriented ‘zero tolerance' policy outlook (Curwin, & Mendler, 1999). Social environment support to reduce loneliness through means such, as peer support programs are vital in the development of prevention programs. An evaluation of components of effective violence prevention programs for 7-14 year olds showed that direct classroom teaching and peer mediation along with family interventions were associated most strongly with the reduction of anger, fighting and conflict management, poor impulse control and lack of social concern (Cooper

(ii) "Social Capital' Social capital refers to features in a social organization such as social networks, expectations, and trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit (Coleman, 1988; Bourdieu, 1986; Putnam, 1993). It is derived from interpersonal relationships and an array of obligations, expectations, information channels and norms within families and communities. "Social capital resides in relationships and social organizations that individuals may use to achieve their interests and that promote positive adjustment” (Hetherington, 1999,p. 177). It is a resource and like other forms of capital can be drawn on or accessed as needed. While limited research has examined possible links between social capital and child wellbeing evidence exists for a link between social capital and school dropout and an increase in child behavior problems (Parcel & Menaghan, 1993; Runyan et al, 1998; Hetherington, 1999). One way to operationalise social capital is in terms of school connectedness. Bonding or connectedness is generally defined as an individual's experience of caring at school and sense of closeness to school personnel and environment (Smith, & Sandhu, 2004). Research indicates that school connectedness is associated with safer behaviors and better health outcomes during adolescence (Hawkins, Catalano, Kosterman, Abbott & Hill, 1999). The research of Murray-Harvey & Slee (2005) has identified a strong positive link between feeling supported by teachers, peers and family and adjustment. Support is significantly related to belonging to school.

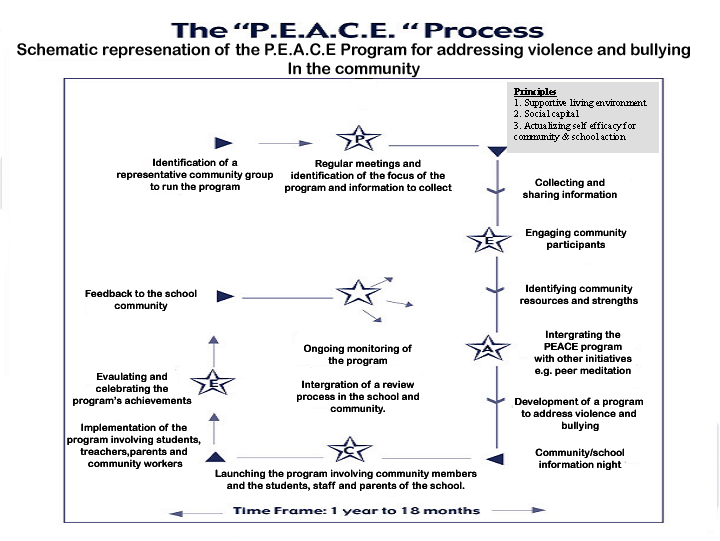

Figure. 4. The relationship between support and psychological health of students (iii) The Actualization of Self Efficacy for Community Action The evidence is that any program to promote, prevent or intervene is significantly strengthened by enabling individuals and groups to participate in the community action. Self-efficacy arises where individuals feel empowered to take control over their daily lives and to be able to influence the decision that affect them. Research into victimization clearly indicates that victims feel powerless and voiceless in the face of violence (Slee, 1993). The very definition of bullying as presented earlier highlights the powerlessness of the victims. Intervention programs should be driven in a ‘bottom up' and not ‘top down' manner such that students and parents are actively engaged in the process. The Five Elements in the School- Community Partnerships These five elements for developing a comprehensive approach to violence prevention and intervention are derived from experience with implementing community programs and from the literature.

"P” PREPARATION In preparing a school violence/bullying programme the Preparation involves identifying a broad based representative group from established schools, organizations and agencies. For example, in the Woodville program participating community organisations included schools, the police department, Catholic Education Office, Department of Education, Training and Employment, and Department of Human Services and Flinders University. Representatives from these organisations meet regularly to co-ordinate an intervention program in a primary and secondary school, which had volunteered to be involved. The purpose of the group must be agreed upon and the focus of the group's work determined. Information is needed regarding the nature of the violence/bullying experience, as a basis for policy development, program development and parent and student involvement and for planning interventions. As previously noted, consideration should be given to where the interventions are targeted such as: (a)universally at whole populations (b)selectively at a population at risk (c)indicatively at ‘high-risk' individuals (a)and (b) are usually identified in terms of ‘prevention' whereas (c) encompasses ‘early intervention'. In the Woodville program the focus was on intervention as the schools/community believed there was a significant issue with school bullying and that it was a particular issue for the primary school involved and particularly the girls. In the ‘5 schools program' the focus was more on prevention with an intention to develop a video for use in schools/community organisations based on identified ‘best practice' principles.

"E” EDUCATION Having prepared the composition of the group and the focus of the program the next step involves educating the group and others about the issue and collecting information upon which to base an intervention

The review of current school practice regarding bullying should provide an understanding of school policy and the nature of the action needed to address the issue of school violence. In the Woodville study a survey was completed involving students from both schools and the findings from this survey provided a basis for developing resources and planning interventions. In the ‘5 schools study a survey was completed, interviews were conducted with teachers, students, and service providers and focus groups run with students to collect information.

"A” ACTION The third step in the P.E.A.C.E. process involves identifying the ACTION that can be taken to address violence and bullying. From a systems perspective, action should engage the various sub-systems of the school environment including students, parents and teachers. A needs analysis can provide insight into existing programs and structures that are already in place in the community. For example in ‘'5 schools program' there were already programs on ‘anger management' running in schools provided for by the local community health organization.

"C” COPING There is evidence that interventions to reduce violence and bullying in schools and communities CAN and DO work as already noted (eg Smith, Pepler & Rigby, 2004). Mishna (2003) has strongly argued that interventions in schools are necessary but not sufficient for addressing the issue of school violence. A stronger focus is needed on working with families and communities. This focus will draw upon the expertise and skills of a broad range of professionals including community workers, social workers, police and school counselors. The broader focus will include promoting community/school safety through addressing attitudes and beliefs that challenge violence, racism, and homophobic beliefs. It will include capacity building to promote social capital in the community to address issues of violence and bullying.

"E” EVALUATION The final step in the P.E.A.C.E. Process involves EVALUATING the effects of any school-based programme for reducing violence/bullying. This may be accomplished using: Surveys If a survey has been conducted then it may be appropriate to conduct a brief follow-up survey to understand the impact of any intervention/program. Interviews Interviews with students, staff, parents and community members following an intervention are another way of evaluating the usefulness of a programme. Observations Examination of records of reported incidents of bullying or direct observations such as in the playground may be useful in evaluating an intervention. Celebration It is important that opportunity be found to celebrate the accomplishments of the whole community/school programme. Avenues that communities and schools have used to achieve this end include: # announcements of progress at school assemblies # class letters circulated amongst classes detailing ideas and accomplishments # school newsletters that are sent home to parents # community information nights # open days at the school which might incorporate a display of the outcomes of the programme e.g. class rules, school policy, etc. # inviting community organizations into schools as part of ‘open days' to present their programs School Violence and Bullying – More Than a Duty of Care As described here the issue of bullying has now broadened to embrace the idea that it is a community issue and not simply a school problem whose responsibility it is to address. It is now understood far more clearly that the issue of violence and bullying is really about relationships. Simplistically, a great deal of research has focussed on the relationship between perpetrator and victim. Now it is understood that the relationship also incorporates the bystanders who witness the aggression and that these bystanders have a very active role to play in encouraging or discouraging it. More broadly still the relationships extend well beyond the school bounds to embrace the family and the broader community. One way to understand why violence/bullying has attracted so much attention in the last few years is to consider the issue from a relationship perspective. It has always been with us, but it is now that the national and international community is beginning to voice its collective concern that it is an unacceptable aspect of human relationships. In sum, the underlying message is that in acting in the best interests of those deemed to be most vulnerable, the community would be seen to be fulfilling its broader civic, social and moral imperatives. Download the PDF file here |

Bibliography

Artz, S., & Riecken, T. (2001). What, so what, then what? The gender gap in school-based violence and its implications for child and youth care practice. Child and Youth Care Forum, 26 (4), 291-303.

Askew, S. (1989). Aggressive behaviour in boys: To what extent is it institutionalised? IN Tattum, D.A. & Lane, D.A. (Eds.). Bullying in schools. Hanley: Trentham Books.

Bjorkqvist, K. Lagerspetz, K.M., Kaukiainen, A. (1992) Do girls manipulate and boys fight? Developmental trends in regard to direct and indirect aggression. Aggressive Behaviour, 18. 117-127.

Bretherton, D, Allard, A., & Cllins, L. (1994). Engendered friendship. : Gender and conflict in after school care. IN K.Oxenberry, K, Rigby & P.T. Slee (eds.) Children's Peer Relations. Cooperation and conflict. Conference Proceedings. 19-22, Jan. Adelaide.

Clearihan S., Slee, P.T., Souter, M., Gascoign,.P., Nicholls, A., Burgan, M., & Gee, J. (2000). Anti Violence Bullying Prevention Project. Victims of Crime Conference. South Australia. Adelaide. 25-26 May.

Coleman . J.S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology. 94, 95-120.

Cunningham, N.J.; Sandhu, D.S. (2000). A comprehensive approach to school-community violence prevention. Professional School Counseling. 4, 2, 126-134.

Curwin, R.L., & Mendler, A.N. (1999). Zero tolerance for zero tolerance. Phi Delta Kappan. October, 119-121.

Commonwealth of Australia (1994) Sticks and Stones:A report on violence in Schools. Canberra Australia Publishing Service.

Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care (2000 a). National action plan for promotion, prevention and early intervention for mental health 2000. Canberra: Mental Health and Special Programs Branch, Comonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care.

Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care (2000 b). Promotion, prevention and early intervention for mental health: A monograph. Canberra: Mental Health and Special Programs Branch, Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care.

Cox, E. (1995). The Boyer Lectures. ABC.

Crick, N. R., Bigbee, M. A. & Howes, C. (1996). Gender differences in children's normative beliefs about aggression: How do I hurt thee? Let me count the ways. Child Development, 67, 1003-1014.

Damon, W. (1984). Social and personality development. New York: Norton and Company.

Debaryshe, B.D. & Fryxell, D. (1998). A developmental perspective on anger: Family and peer contexts. Psychology in the Schools. 35, 205-216.

Debarbieux, E., Blaya, C., & Vidal, D. (2003). Tackling violence in schools. A report from France. IN P.K. Smith (ed). Violence in schools. The response from Europe. Pp17-32. Routledge Falmer. London.

Elsea , M. & Smith, P. (1998). The long-term effectiveness of anti-bullying work in primary schools. Educational Research., 40, 2, 203-218.

Etzioni, E. (1995). New communitarian thinking, persons, virtues, institutions, and communities. University Press, Virginia.

Frodi, A., Macauley, J. & & Thorne, P.R. (1977). ‘Are women less aggressive than men? A review of the experimental literature. Psychological Bulletin, 84. 634-660.

Gilbert, R., & Gilbert, P. (1998). Masculinity goes to school. St. Leonards, NSW: Allen and Unwin.

Hawkins, J., Catalano, R. F., Kosterman, R., Abbott, R & Hill, K.(1999) Preventing adolescent health-risk behaviours by strengthening protection during childhood. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 153, 226-234.

Hawker, S.J. & Boulton, M. (2000). Twenty years' research on peer victimisation and Psychosocial maladjustment:A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 41, 4. 441-455.

Hemphill, S.A., Toumbourou, J.W., & Catalano, R.F. (2005). Predictors of violence, antisocial behaviour and relational aggression in Australian adolescents. A longitudinal study. A report for the Criminology Research Council.

Howe, R & von Foerster (1974). Introductory comments to Francisco Varela's calculus, For self reference. International Journal of General Systems, 2, 1-3.

Hudley, C., Wakefield, W.D., Britsch, B., Cho, S-J., Smith, T., & DeMorat, M. (2001). Multiple perceptions of children's aggression: Differences across age, gender, and perceiver. Psychology in the Schools, 38 (1), 43-56.

Lerner, R.M., Fisher, C.B. & Weinberg, R.A. (2000). Applying developmental science in the 21st Century. : International scholarship for our times. International Journal of Behavioural Developmeny. 24. 24-29.

Mishna, F (2003). Peer victimization: The case for social work intervention. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services. 84, 4, 513-522.

Mooij, T (2005). National campaign effects on secondary pupil's bullying and violence. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 75. 489-512.

Morita, Y. (1985) (ed.). Ijime Syuudan no Kouzou nikansuru Syakaigakuteki Kenkyu (Japanese) [Sociological Study on the Structure of Ijime Group] Osaka: City College Sociology Study.

Murray-Harvey, R. & Slee, P.T (2006). Australian and Japanese school student's experiences of school bullying: Associations with stress, support and school belonging. Paper presented at IIIrd International Conference on Violence ins Schools. Bordeaux. Jan 12-14th.

Olweus D. (1993). Bullying in schools:What we know and what we can do. Oxford. Blackwell

Murnen, S.K., & Smolak, L. (2000). The experience of sexual harassment among grade-school students: Early socialization of female subordination? Sex Roles, 43 (1/2), 1-17.

Owens, L. (1996). Sticks and stones and sugar and spice: Girls' and boys' aggression in schools. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 6, 45-55.

Owens, L. (1998). Physical, verbal and indirect aggression amongst South Australian school students. Unpublished PhD thesis, School of Psychology, The Flinders Univesity of South Australia.

Owens , L. Shute, R., and Slee, P. (2000 a). "Guess what I just heard...” Indirect aggression amongst teenage girls in Australia. Aggressive Behavior, 26, 67-83.

Owens, L., Shute, R., & Slee, P. (2000 b).”I'm in and you're out…” Explanations for girls' indirect aggression. Psychology, Evolution and Gender, 2 (1) 19-46.

Owens, L. Slee, P. and Shute, R. (2000) "It hurts a hell of a lot...” The effects of indirect aggression on teenage girls. International Journal of School Psychology, 21 (4), 359-376.

Owens, L., Slee, P., & Shute, R. (2001). Victimization among teenage girls. What can be done about indirect harassment?. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds), (pp. 215-241). Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York: Guilford.

Parcell, T.L. & Menaghan, E.G. (1993). Family Sdocial capital and children's behaviour problems. Social Psychology Quarterly. 56. 120-135.

Paquette, J. A. & Underwood, M. K. (1999). Gender differences in young adolescents' experiences of peer victimization: Social and physical aggression. Merril-Palmer Quarterly, 45 (2), 242-266.

Randall, P. (1995). A factor study of attitudes of children to bullying in a high risk area. Educational Psychology in Practice, 11, (3) 22-27.

Randall, P. (1997). A community approach to bullying. Trentham Books. London.

Rigby, K & Slee, P.T (1991). Bullying among Australian school children: Reported Behaviour and attitude towards victims. Journal of Social Psychology, 131. 615-627.

Rigby. K & Slee, P.T. (1999). Suicidal ideation among adolescent schoolchildren, Involvement in bully/victim problems and perceived low social support. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behaviour.

Rigby, K., & Slee, P. (1999). The nature of school bullying: Australia. In. P.K. Smith, Y. Morito, J. Yunger-Tas, D.Olweus & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: A cross-national perspective. London: Routledge.

Rigby, K & Slee, P.T. (1991). Bullying among Australian school children: reported behaviour and attitudes to victims. Journal of Social Psychology. 131. 615-627.

Roland, E., Bjornsen, G., & Mandt, G. (2003) ‘Taking back adult control: A report from Norway. IN P.K. Smith (ed). Violence in schools. The response from Europe. Pp.200-216. Routledge Falmer. London.

Runyan, D.K; Hunter, W.M.; Socolar, R.R.S.; Amaya-Jackson, L.; English, D; Landsverk, J.; Dubowitz, H; Browne, D.H.; Bangdiwala, S.I, & Mathew, R.M. (1998). Children who prosper in nfavourable environments: The relationship to social capital. Pediatrics,101, 12-18.

Russell, A. & Owens, L. (1999). Peer estimates of school-aged boys' and girls' aggression to same- and cross-sex targets. Social development, 8, (3), 364-379..

Salmivalli, C. Lagerspetz, K. Bjorkqvist, K., Osterman, K. & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22, 1-15.

Sebastiao, J., Campos,J., & deAlmeida, A.T. (2003). Prtugal: the gap between the political agenda and local initiatives. IN P.K. Smith (ed). Violence in schools. The response from Europe. Pp119-135. Routledge Falmer. London.

Shonkoff, J.P. (2000). Science, policy and practice: Three cultures in search of a shared mission. Child Development. 71, 181-187.

Slee, P.T. (2001) (3rd. edt.). The PEACE Pack. A program for reducing bullying in our Schools. Flinders University. Adelaide.

Slee. P.T. (1995). Bullying:Health concerns of Australian secondary school students International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 5. 215-224.

Slee, P.T. & Shute, R. (2003).Child development: Thinking about theories. Arnold. London.

Smith, P.K.; Morita, Y.; Junger-tas, J.; Olweus, D.; Catalano, R.; & Slee, P. (1999) The nature of school bullying. A cross-national perspective. Routledge. England.

Smith P.K. (ed.) (2003). Violence in schools. The response in Europe. Routledge Falmer. London.

Smith, D.C. & Sandhu, D.S. (2004). Toward a positive perspective on violence prevention in schools: Building connections. Journal of Counseling and Development. 82, 287-295.

Taki, M. (2001). Relation among bullying, stress and stressor: A follow-up survey using panel data and a comparative survey between Japan and Australia. Japanese Society, 5, 25-41.

Tam. H. (1996). Education and the communitarian movement. Pastoral Care in Education.. 14. 3.

Tulloch, M. (1995). Gender differences in bullying experiences and attitudes to social relationships in high school students. Australian Journal of Education, 39, 279-293.

Webber, J. (1997). Comprehending youth violence. A practicable perspective. Remedial and Special Education. 18. 2. 94-104

Read also

> Editorial

> Dynamique démocratique et violence scolaire

> Keeping Violence in Perspective

> La violence au préscolaire et au primaire : Aperçu de la situation canadienne

> Revues systématiques dans le champ criminologique et le groupe crime et justice de la collaboration Campbell

> The Effectiveness of School-Based Violence Prevention Programs for Reducing Disruptive and Aggressive Behavior: A Meta-analysis

> Violence in school: a few orientations for a worldwide scientific debate

<< Back